"Little Mexico"

A few years before I began pursuing my university degree, I worked at a potato factory in Eastern Idaho.

For thorough-bred Idaho natives (such as myself) this is a rite of passage alongside laying irrigation pipe and participating in the spud harvest, and I learned a lot and grew a lot in that rugged environment.

If you’ve never been inside an industrial potato plant, you’re missing out. Eastern Idaho is home to a classic model of massive factories filled with shiny assembly line machinery. The sheer amount of potatoes shipped into the factory from the farmland is staggering, and the factories simply never stop churning out potato products, whether it’s the middle of winter or the height of the summer.

Early on in my time there, I was waiting my turn in line to bag 50 pounds of raw potatoes when a small group of my co-workers began to gesture first toward me and then to a large whiteboard hanging on the wall. One of the supervisors (whom we rarely saw outside of the administrative offices) had just posted the daily goals for the various divisions of the factory, and this seemed to be the reason why these co-workers were gesturing toward me. They seemed a bit upset, which unsettled me and prompted me to ask one of my Spanish-speaking friends what was happening.

He informed me that the small group of my co-workers were questioning why the information on the whiteboard was always written in English. After all, they said, “Da-veed” (meaning me) is the only person on the entire floor who speaks English – all the rest of the workers spoke Spanish.

I hadn’t really been aware of my status as such an obvious minority, but I began to look around to see if it was true and quickly realized I was in the middle of a “little Mexico.” The fact didn’t bother me in the least. I had made friends there very quickly, despite the language barrier, and moreover my work friends and I enjoyed teaching each other how to communicate in our respective languages whenever we had the chance. In brief, I was making good living and growing in more than one way.

At the same time many good things were happening, there were also some well-established workers within the factory community who really seemed to dislike my presence. Someone once advised me to find a different job, saying: “Why do you work here? You should find a job in Idaho Falls, then you won’t have to commute.” My commute was only 20 minutes – not a problem at all – but some were eager to get rid of me.

In all honesty, their opposition and resistance to my presence as a manual laborer hurt me, and I wanted to know why. I had already decided to work as hard as I possibly could, for a variety of reasons, but my minority status gave me new incentives to excel at my job.

To start with, a large part of our job was to stack pallets 8 layers high, as large bags of potatoes issued from sophisticated and dangerous packaging machine. It was hard work. Accordingly, the practice was for us to rotate between the palletizing and a different task of filling mesh bags one at a time, or else we would be quickly drained and exhausted by the time lunch rolled around.

My fellow workers were of a variety of ages and sizes. One fellow was 72 years old – everyone called him “Abeulo” which means “Grandpa.” He was short and very spirited despite his age, and more importantly, he was motivated to work in support of himself. At an age when he ought to have been in retirement, he was forced to labor in the workforce as best he could.

One day, when I realized that "Abeulo" was next in line to begin the hard work of palletizing after my turn, I waved him away and continued to stack. It didn’t feel right for me to covet a breather when I could reasonably bear the burden for this poor man; and so I exerted myself and doubled my workload (probably as much out of pride as compassion, if I’m being honest).

This became my practice with every rotation I took, no matter who was supposed to take their turn after me. I thought I was ingratiating myself with my fellow workers, showing them that I was “one of them,” engaged in our hard labor together.

Yet curiously enough, my approach backfired in some ways.

Some of my fellows saw me as competition on the path to promotion, which simply wasn’t true. I didn’t have any ambition to coordinate or organize work in the potato factory; in fact, I had taken the job partly because of its simplicity for me. I knew I could stack potatoes, and my long-term goals for employment ended at paying for my apartment and funding my tuition.

Another time, the lead supervisor for all the work in the factory began call me “Boy” whenever I was around him and a group of people. He would address me derisively and in an unnecessary way, emphasizing my youth and inexperience by going out of his way – yet in private he did NOT treat me in any negative way, which provoked my ego and weakness as it became a pattern. At first I tried to ignore the nickname, but eventually I confronted him off the side of our work site and told him somewhat forcefully: “With all respect, don’t call me ‘Boy’ anymore; I find it insulting and I want you to stop.” He complied with my request and I was surprised to find that our conversation hadn’t hurt my working relationship with him – instead it helped it, at least to a small degree.

There was another group of leaders in the factory, four brothers, all with shaved heads, who truly disliked me. I didn’t know the reason at the time, but through conversations with my friends and acquaintances in the workplace, I discovered their belief (or accusation) that I was an uncover police officer working for ICE or an immigration task force. Of course, this rumor displeased and worried me, as it wasn’t true; but it explained why some of my fellow workers were opposed to me as a matter of principle, no matter what I did or how I behaved myself toward them.

One of the brothers directed the work of palletizing, running the machines through computer screens and barking orders to us and others on the factory floor. He monitored the performance of the machines, and would often hover by the palletizers with all the force of his authority at bear.

His appearance was striking, as he was probably the tallest and largest worker there (apart from myself – I had a 4 or five inches on him). One of his eyes lacked a pupil or iris, and he usually wore an eyepatch to cover it. All of his intensity and intelligence came spilling out of his one eye, and he was a formidable presence, respected by everyone.

In the midst a whirlwind of rumors about the reason for my presence among the factory workers, this particular man began to work to intimidate me – something which I admit worked. I found myself frightened of him and didn’t like being around him. Every word I spoke to him felt like a fight waiting to happen.

One day, he decided to assume a posture of intimidation against me, punching one of his gloved hands into the other in a classic show of threatening force, while he actually walked behind me much closer than was necessary, invading my personal space. I reeled beneath the fear I felt for the better part of an hour, until my fear turned into anger and bubbled out of me. When the English speaking owner of the factory passed through and stopped to talk with the gloved intimidator, I quickly approached and expressed my feelings and intentions to both of them, respectively and at the same time: “This guy has been threatening me, punching his glove and glaring at me – and believe me, I’ve been in fights before; I know what physical conflict feels like and I promise you (turning to the worker/supervisor) if you want a fight I’ll give you one!”

Somehow, miraculously, I wasn’t fired for my outburst. The owner actually reassured me that the man had worked there for 9 years. They knew and trusted him; in short they found no fault with him and actually valued him highly.

Now, in hindsight, my experience speaks to the “wild west” atmosphere of that particular workplace. I wasn’t fired or disciplined, and neither was the man. Instead, we were left to settle our differences despite the threat and possibility of violence – something I embraced at the time as a form of freedom.

On the other hand, I also remember and cherish many conversations with Spanish peers of my own age (meaning early 20’s to 30’s). I noticed a common regard for the Virgin Mary, which was evidenced in her full image on their arms, or the Cross of Jesus around their neck.

I was curious as to why a young person of their culture would seek out such a religious image to be the most prominent feature of their appearance, and so I asked as I gained the language skill to do so.

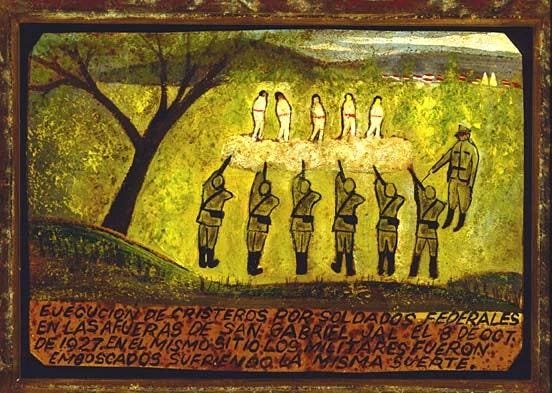

Eventually, I discovered an astonishing feature of Mexican history and culture, namely a domestic war over “Religious Freedom” which had been waged in Mexico at the beginning of the 20th century. In short, an atheist President had taken power and immediately outlawed the Catholic Mass, going so far as to punish Priests for wearing frocks and collars in public. In response, the devout husbands and fathers of the Catholic faith in Mexico had mounted a militant opposition, choosing a general and outfitting an army to wage war against the Federal Government of Mexico on the single issue of their “Religious Freedom.”

Between 1926 and 1929, the “Cristeros War” (as it is called) took the lives of 56,882 federal officers and 30,000 of the “Cristeros” fighters, only ending after the Vatican disavowed the religious resistance. Many brave Mexicans met a martyrdom in that land, and their blood was shed in the name of their earnest and heartfelt faith in Jesus Christ. The co-workers and friends I met at the potato factory were descendants and inheritors of that great legacy, hence their allegiance to “the Virgin of Guadalupe” and the person of Jesus Christ.

My respect for the Mexican People was multiplied ten-fold when I discovered their buried history and the legacy of true valiance it entailed.

Eventually, my university courses took priority in my life and I began a part-time schedule at the potato factory, which ended when I sustained a minor injury on my hand from one of the packaging machines. My departure was mostly sad, and I felt a hole in my life after leaving. I would like to think the year I spent at the factory had earned me the respect of my fellows; which may or may not be the case – but I did leave with a sizeable Spanish vocabulary thanks to my new friends, something I am proud of to this day.

I am making mention this chapter of my life now, at a time when a “border crisis” flood of illegal aliens is pouring over the Mexican-American border, settling in communities like the one I encountered here in Eastern Idaho. Many “little Mexico’s” exist outside of the sight of most of society, filled with a wide variety of social dynamics, families, leaders, and dreams of a better life here in the “Promised Land.”

Some of these immigrants are good people, who I am proud to call friends; others are wrapped up in the hellish consequences of the “Cristero War,” which turned Mexico into a no-man’s land and made resistance to Federal Authority a matter of “Greater Glory” and honor, giving room and precedent for the authority and violence of the modern cartels.

On this front – meaning the “righteousness” of illegal immigration - my judgment is imperfect. But I do know the prophecies of Lehi, a great Patriarch and Prophet of this land:

“Wherefore, I, Lehi, prophesy according to the workings of the Spirit which is in me, that there shall none come into this land save they shall be brought by the hand of the Lord.

Wherefore, this land is consecrated unto him whom he shall bring. And if it so be that they shall serve him according to the commandments which he hath given, it shall be a land of liberty unto them; wherefore, they shall never be brought down into captivity; if so, it shall be because of iniquity; for if iniquity shall abound cursed shall be the land for their sakes, but unto the righteous it shall be blessed forever.” – (2 Nephi 1: 6-7)

The truthfulness of this prophetic utterance is borne out in the fact that the political “Right” has been powerless to stop this supposed “invasion.” In other words, the proof is in the pudding and these people are here – probably to stay.

What purpose will be accomplished by this? Only the scriptures can say…